“. . until when he (eventually) came to (a land which was the farthest

point eastwards that he could go since there was no land beyond and it

appeared like the end of the Earth) and that the sun was rising from

beyond that land; he found it rising on people for whom We had provided

164

no covering (i.e. perhaps no protection against the sun (climate,

atmospheric pollution etc.) other than the natural covering).

(Qur’ān, al-Kahf, 18:90)

The stretch of land for which we are looking must not only be

bounded on both west and east by two large seas but must also be

geographically characterized by impassable continuous mountain

range. We need to find a series of more or less connected

mountains ranged in a line stretching from the shores of one sea

to the other. Only thus can we accept that the construction of a

barrier blocking a solitary pass between the mountains could

effectively seal off the passage of marauding tribes from one side

of the mountain range to the other side:

“And thus (the barrier was built and Gog and Magog) were unable to

scale it and neither were they able to penetrate it (by digging a hole

through it) (and these had to be the only two options available to them

since Dhul Qarnain proceeded to declare that the construction of the

barrier was an act of Divine Kindness, i.e. implying that mankind was

henceforth safe from the ravages of Gog and Magog).”

(Qur’ān, al-Kahf, 18:97)

Dhul Qarnain used the Arabic word Radmun to describe the

barrier which he was going to construct. While Saddun in Arabic

means barrier, Radmun implies a construction which fills up a

space akin to a dam. Let us repeat; we must look for a geographical

region North of the Holy Land which is bounded on both west and

east by large seas, with the Western sea characterized by a dark

color. Between those two seas there must be a continuous

unbroken impassable mountain range that is relieved by a single

gap or mountain pass allowing passage of people from north to

south and vice versa. The Qur’ān has described the very shape of

the two sides of that mountain pass to be akin to an open sea-shell,

i.e. the two sides of an open sea-shell that are joined at the bottom

and separated at the top:

“Bring me ingots of iron!” Then, after he had (piled up the iron and)

filled the gap between the two mountain-sides (shaped like two sides

of an open sea-shell), he said, “(Light a fire and) ply your bellows!”

At length, when he had made it (glow like) fire, he commanded:

“(Now place the copper in the fire and then) bring me molten copper

which I may pour upon it . . . .”

(Qur’ān, al-Kahf, 18:96)

When we search north of the Holy Land for large bodies of

water we immediately dismiss the Mediterranean Sea and the area

east of that sea since they do not fit any of the above descriptions.

That leaves only one other possible answer; and it fits all the

descriptions perfectly.

North of the Mediterranean Sea is the ‘Black Sea’. A possible

explanation for the name ‘Black Sea’ is located in the unusually

dark color of its deep waters. Being further north than the

Mediterranean and much less saline, the microalgae concentration

is much richer causing the dark color. Underwater visibility in the

Black Sea is much less than the Mediterranean Sea. The satellite

photograph of the Black Sea in Map 1 below readily depicts that

dark color. It should therefore be quite clear that the Sea to the

West in Dhūl Qarnain’s travels cannot be other than the Black Sea

Once we recognize the Black Sea to be the sea located at the

Western end of Dhūl Qarnain’s travel, the sea to the right would

then be the Caspian Sea

In between these two seas are located the Caucasus

Mountains. Indeed this mountain range stretches from one sea to

the other and in the process it separates Europe from Asia

Now that we have located the two seas as well as the

mountain range that extends all the way from one sea to the other,

we have to find a solitary pass between the mountains and

evidence of iron from the ruins of Dhūl Qarnain’s barrier. Sure

enough, the Georgian Military Highway that was built by the

Russians in the 19th century is the only passable road that connects

the area north of the mountains to the southern area. It is the main

169

road running for 220km from Tbilisi in Georgia to Vadikavkaz in

Russia. So named by Tsar Alexander I, this route actually dates

from before the 1st century BC and is still important as one of the

only links to Russia through the Caucasus Mountains.

Information readily available on the internet describes it as “a

spectacular highway, which winds its way through towering

mountains, climbing to above 2300m at the Krestovy pass.

Heading north from Tbilisi one first reaches the medieval fortress

of Ananauri, overlooking the Aragvi river and valley. Nearing the

Russian border, one comes to the town of Kazbegi, overlooked by

the monumental Mount Kazbegi (5033m), the highest peak in the

Georgian Caucasus. The last point is the Daryal Gorge, where the

road runs some kilometres on a narrow shelf beneath granite cliffs

1500m high.” “Daryal was historically important as the only

available passage across the Caucasus and has been long fortified

at least since 150 BC. Ruins of an ancient fortress are still visible.”

We have now located the pass between mountains and it now

remains for an archaeological search to be made for the remains of

the barrier. Dr Tammam Adi has pointed out in personal

correspondence with this writer: “I would expect any leftover

debris (i.e. of the barrier built by Dhūl Qarnain to be at the bottom

of the gorge and to be made of bronze, an alloy of iron and

brass/copper, as the verse clearly states”. We must also look for

evidence of iron ore in and around the region south of the

Caucasus Mountains since that is where the people would have had

to locate the iron to bring pieces or blocks of iron for Dhūl

Qarnain.

The Wekipedia article on Daryal Gorge which incorporates

text from Encylopedia Britannica (11th edition) locates the origin of

the name of the Gorge in Dār-e Alān meaning Gate of the Alans in

Persian. The Gorge, alternatively known as the Iberian Gates or

the Caucasian Gates, is mentioned in the Georgian annals under

the names of Ralani, Dargani, Darialani.” In other words, the name

Daryal has preserved the historical fact of some form of a barrier

constructed from metal that once existed in that Gorge.

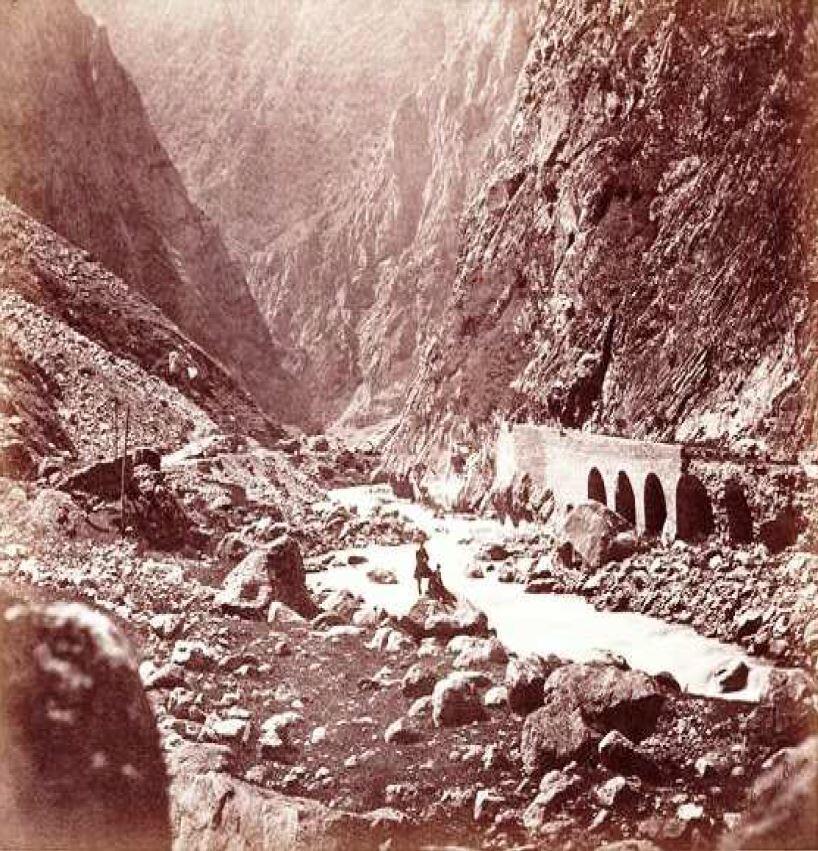

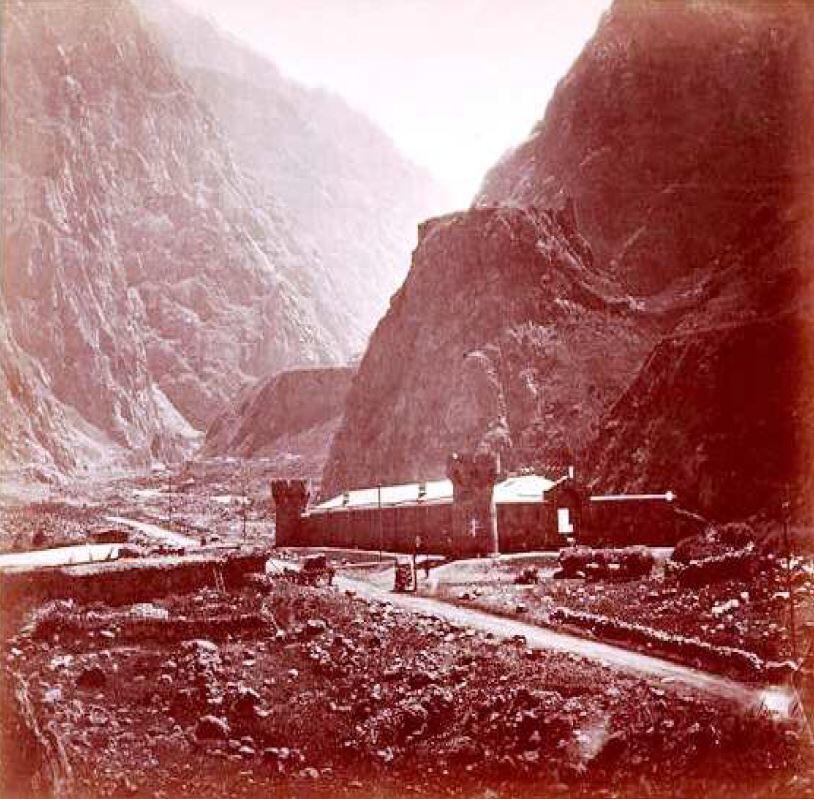

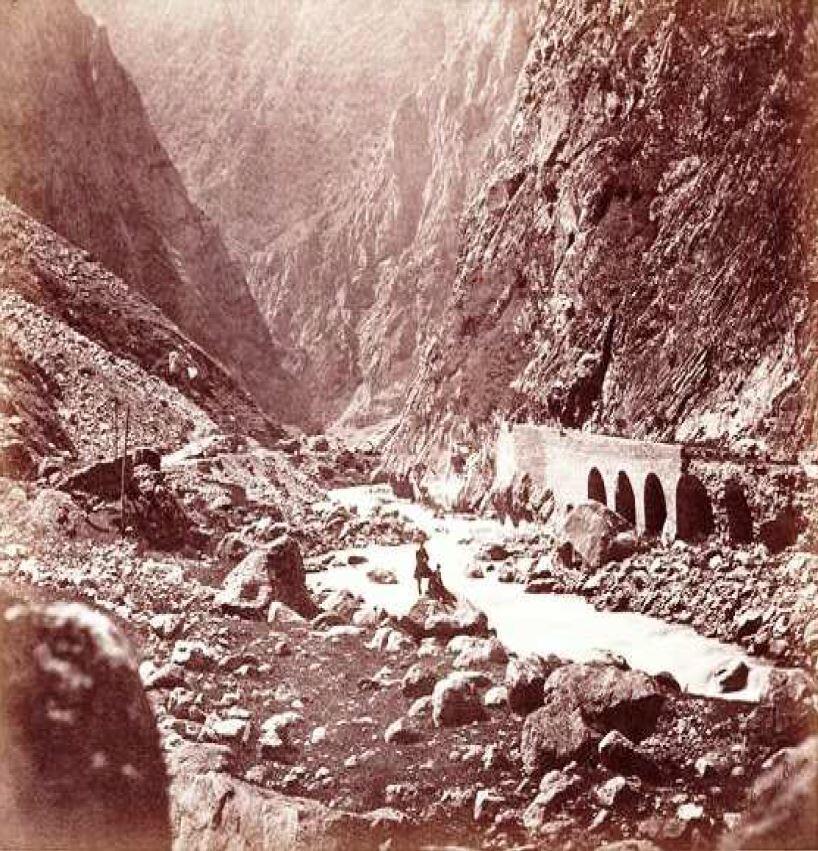

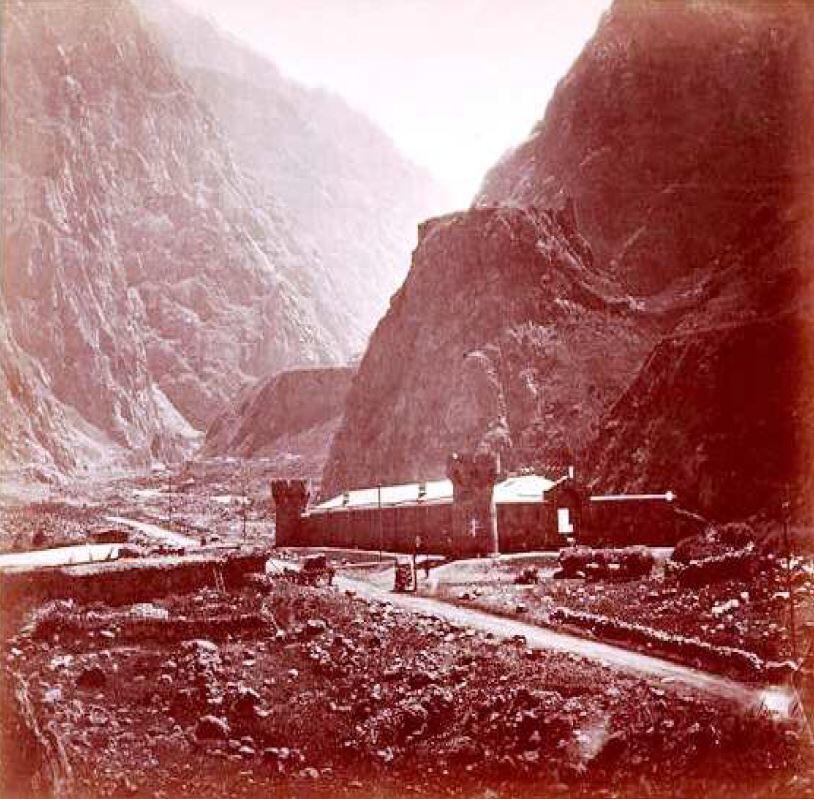

Finally the mountain sides on both sides of the Daryal Gorge

are shaped like two sides of an open sea-shell exactly as described

by the Qur’anic word Sadafain. Here are photographs of the Daryal

Gorge taken 1872:

Here is a photograph of an open shell showing its

sadafain i.e. two sides joined at the bottom and separated at

the jagged top, and then two more photographs which clearly

depict the sadafain or shell-shaped features (i.e. two sides of

an open shell) of the Gorge

We also have to find a language spoken south of the Caucasus

Mountains, which is different from all the other languages spoken

in and around that region of the then known world. We need to do

so because of Dhūl Qarnain’s experience when he arrived at that

location and found people who could not understand his language:

“(And he marched on) till, when he reached (a pass) between the two

mountain-barriers, he found before them a people who could scarcely

understand anything spoken (i.e. any utterance in his language).

(18:93)

Sure enough, the Georgian language which is spoken south of

the Caucasus Mountains is precisely such a language. It is an

insular pre-Indo-European language with no relatives that has been

spoken for at least 5000 years.

Tembok sudah hancur!